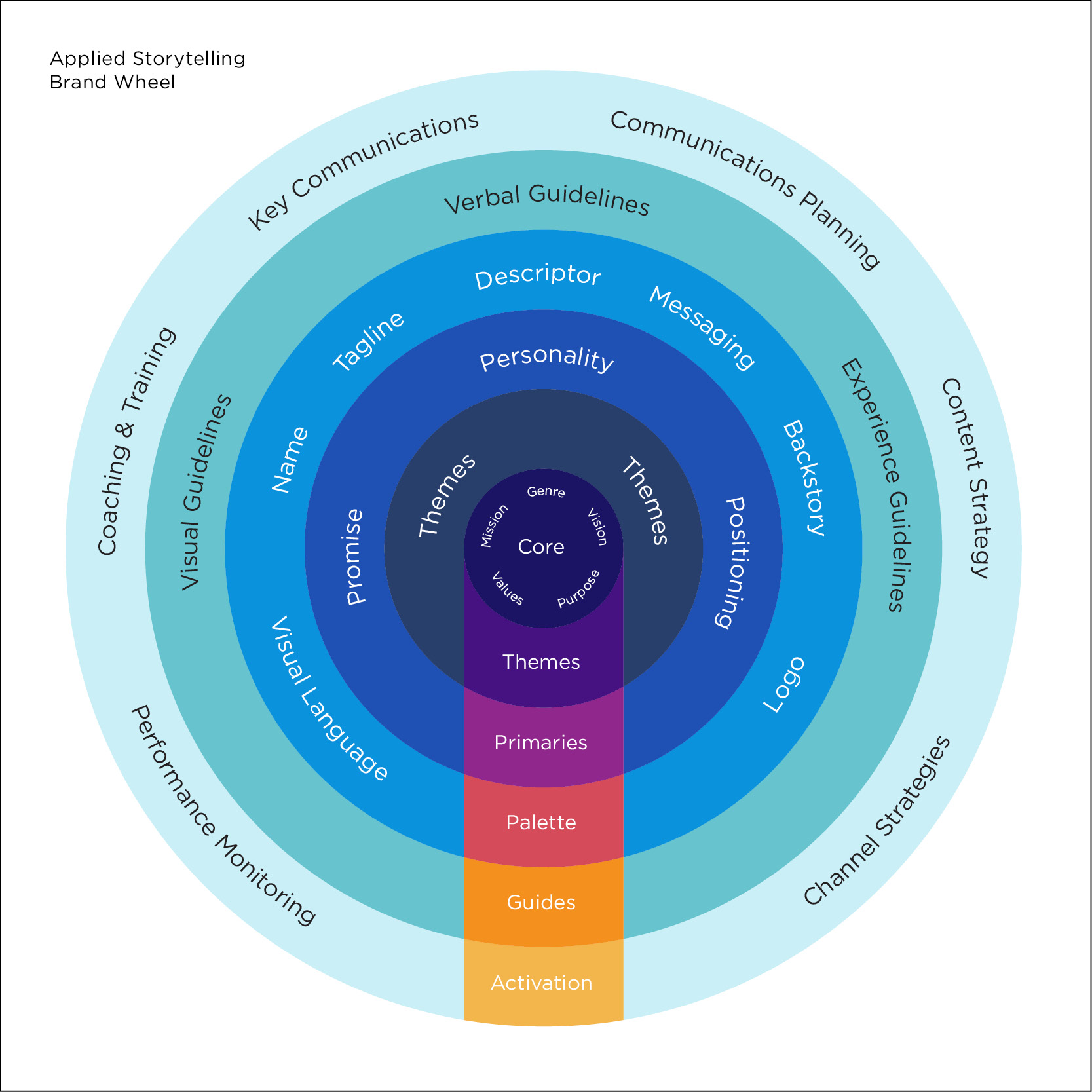

When we set out to build a foundation for telling a brand story, we develop and organize the building blocks of the story with a specific framework in mind. We call this framework the brand wheel. It’s something we cooked up for ourselves back in the late 90s, a good decade or so before the idea of storytelling as a marketing activity really took off, because we needed a tool that simply didn’t exist at the time. The brand models of the day, some of which still enjoy wide circulation, weren’t based on the underlying idea of the brand as a story told in the marketplace.

While we’ve refined the brand wheel in many ways over the years—and others have gone on to adapt it to their own sensibilities—the current iteration of the brand wheel would still be intelligible to our earliest brand strategy clients (some of whom have remained with us for the duration). If anything, in a world that increasingly sees the value of storytelling applied in a market context, the wheel seems more useful than ever.

We’ve had good results with the brand wheel. A number of our peers have also put it to good use. Our clients, too, have found the brand wheel to provide welcome clarity. Many have internalized it. Yet we’ve been remiss in sharing it widely. With the advent of our podcast, Brand Frontlines, which considers the brand wheel in depth and explores brand storytelling more generally, we can’t shirk our responsibilities any longer.

Overview

The brand wheel is arranged in a series of concentric rings. Elements at the center are the ones we develop first. Elements in each ring lay the groundwork for those in the next ring. As a general rule, elements in rings closest to the center change least often and are the least public-facing.

Elements in the outer ring are changing all the time. The outer ring is permeable. Beyond it lives the marketplace, and beyond that the world at large, where the story gets told, shared, retold, modified by customers and others, and so on. Ideally, the transmission of ideas and information from the core to the world and back again is dynamic and ongoing.

In addition to using the brand wheel as a guide to building or updating brand stories, we use it as a tool for assessing the state of existing brands. When a client with an existing brand communications framework comes to us, we use the brand wheel to quickly ascertain where certain story elements might be missing, where certain elements might be out of alignment with each other, whether certain elements are inherently sound, and where certain elements might be out synch with our client’s current business or strategic plan—which the brand exists to serve, after all.

Introducing the Elements: A Tour of the Rings

Before we take a closer look at the brand wheel, a quick note about terminology: Many of the terms we use (for example: positioning, promise, personality) are standard among marketers, even if their definitions vary a bit from marketer to marketer. Other terms that we use hail from the world of storytelling (for example: genre, themes, backstory). Over time, we’ve tended to substitute story-centered terms for marketing-centered ones. So, for example, while “brand drivers” is more familiar to our peers, “themes” is more in line with our way of thinking about brands.

The Core: Vision, Mission, Values, Purpose, Genre

First, an admission: Four of the five elements we’ve located in the core—purpose, vision, mission, and values—live there out of sheer convenience. (Genre is another matter.) While these are absolutely critical to our work, in our dreams our client has already defined them before we show up. Their value extends beyond brand-building. Each has a mutually supportive role to play in setting business strategy and building a strong organization. That said, we often find these elements—even the vision and mission statement—to be missing or off-base when we perform our initial due diligence. And so our work frequently begins there.

We define the vision as a statement of the ultimate outcome an organization pursues or impact it seeks to make. Vision statements lead endeavors into the future with clarity and purpose. As with most brand fundamentals, a good vision statement is short—a phrase or a sentence, and not a run-on one at that. More importantly, a good vision statement is, well, visionary. If it describes something that’s already the status quo, it’s not a vision statement. The best vision statements are bold. They’re capable of powering an organization forward for years, if not indefinitely. Our vision statement for the City of Dearborn exemplifies these qualities: “One of the most desirable cities in the United States in which to live.”

From a storytelling standpoint, the vision is super-important. It describes the story’s motivating action and drives that action forward.

The mission statement succinctly sets forth how an organization will realize its vision. Often this simply comes down to summarizing what’s being offered, and to whom. Many organizations confuse vision and mission, or don’t see the need for one or the other. (We once encountered a prospective client that didn’t see the need for either. We declined the project.)

A simple example from literature might help to clarify the relationship between vision and mission: In The Odyssey, at the conclusion of the Trojan War, Odysseus is motivated by a vision of home. He pictures his wife and son and the peaceful life he yearns to resume. With this vision constantly before him, he sets out on a mission to build a boat, find a crew, chart a course, and make his way back to his native Ithaca. His mission will ultimately require ten years to fulfill.

The purpose, or why statement, is a core element, that has gained traction in recent years largely through the work of Simon Sinek. He makes a compelling case for defining an organization’s (or one’s own) purpose in his book Start With Why. In line with Sinek’s thinking, we see this element as a statement that sets forth an organization’s higher reason for being or inner motivation for doing something. This reason transcends money. As the title of Sinek’s book suggests, understanding why should happen at the start of business or brand development, even before nailing down the vision and mission.

While we heartily recommend introspection into higher purpose and inner motives, and while we do often find a need to work from a why statement, I confess to not always crafting one. For one, in the boldest vision statements we’ve seen or developed, the why often seems baked in or self-evident. We’re still in the midst of talking over the place of the purpose with others and working it out for ourselves.

For our purposes, values are central beliefs grounded in the truth of the organization and expressing its highest aspirations. From a practical standpoint, values guide the decisions and behaviors that aid in carrying out the mission. They also inform an organization’s culture. From a storytelling standpoint, values also inform plot developments.

A good set of values is manageable in number—three to five, generally speaking. A good set of values also feels right together, capable of being taken up by real people, and bearing some relation to the organization’s history, partner and customer relationships, people, and leadership. That said, leaders can develop an under-lived value or even introduce an entirely new one so long as they’re committed to nurturing it. We’re working with a company right now that is looking to elevate curiosity as a value it wants to instill in its organization’s DNA.

As noted earlier, if we were representing the model in three dimensions rather than two, we’d present the core elements I’ve just talked about as being somewhere below or behind everything else. For the longest time, we showed only a single element at the core: the genre.

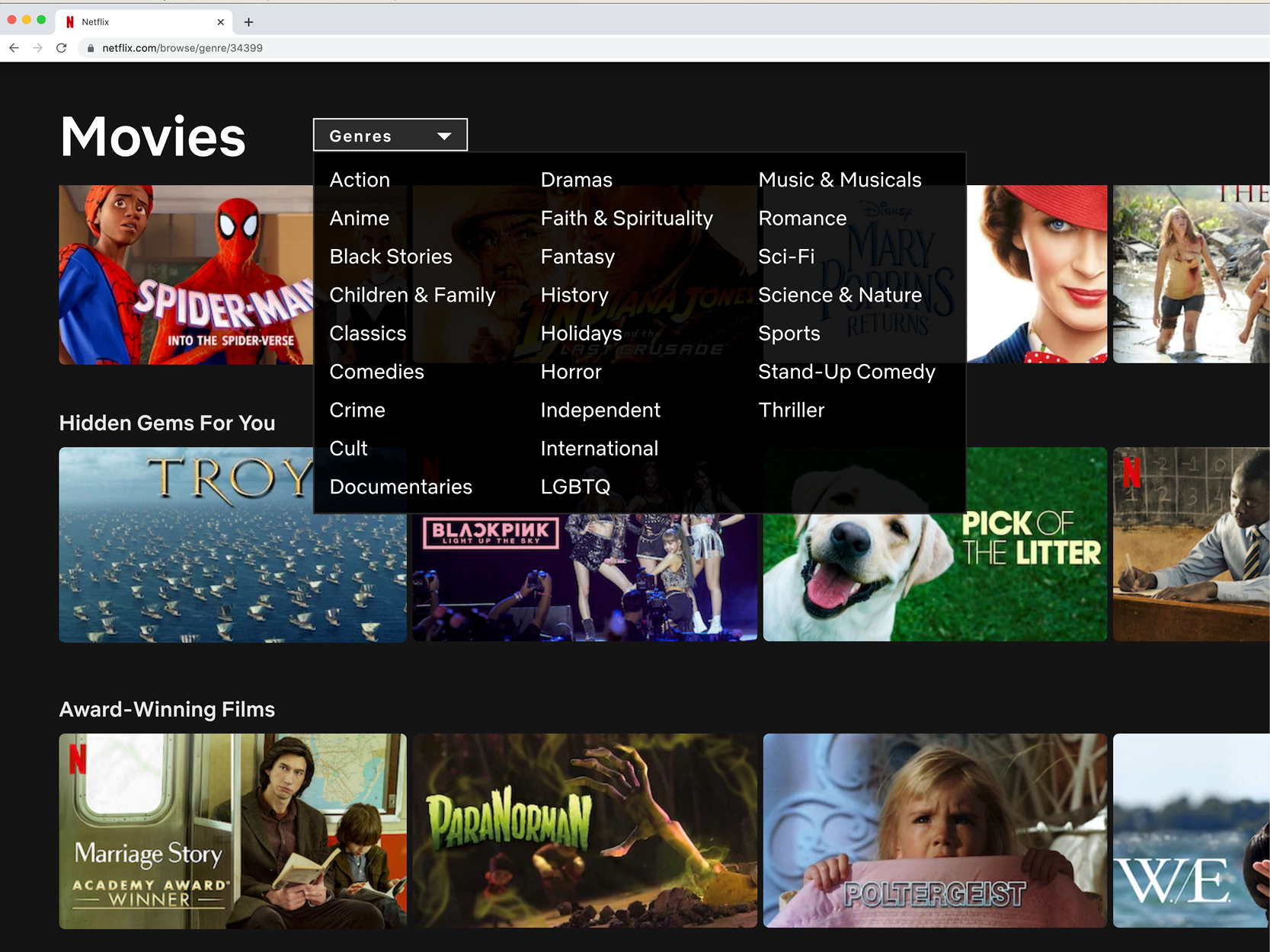

For us, it’s with the genre that story development really gets underway. What we call genre is familiar to most marketers as “brand essence.” more or less. While we’ve settled on “genre” only recently, we moved away from “brand essence” several years ago. (In between, we tended to call this element the “core.”) Clients who weren’t grounded in marketing seemed to have a hard time understanding what “brand essence” meant. “Genre”they understand. In the context in which we’re using it, “genre” describes a category of story defined by a particular type of content. In movies, genres include Sci-Fi, Adventure, Western, Rom-Com, and so on. In brand storytelling, genres double as categories of business: Discount Retail, Endpoint Security, Cultural Institution, and so on.

Defining the brand genre establishes broad expectations about the story an organization wants to tell. The genre helps customers to place a given story among others broadly similar to it. The genre of a story doesn’t change (at least, not very often). Every product, service, and initiative offered by an organization ideally embodies its genre. If you tell things or sell things that are out of step with your genre, your story risks confusing and losing people.

First Ring—Themes

Good stories develop a few well-defined themes. The Odyssey, for example, explores themes of return, wandering, friendship, hospitality, and resolve. Brand stories are no different, except that list of possible themes is nowhere near as wide-ranging. We generally look to identify three to five themes that follow from the brand core.

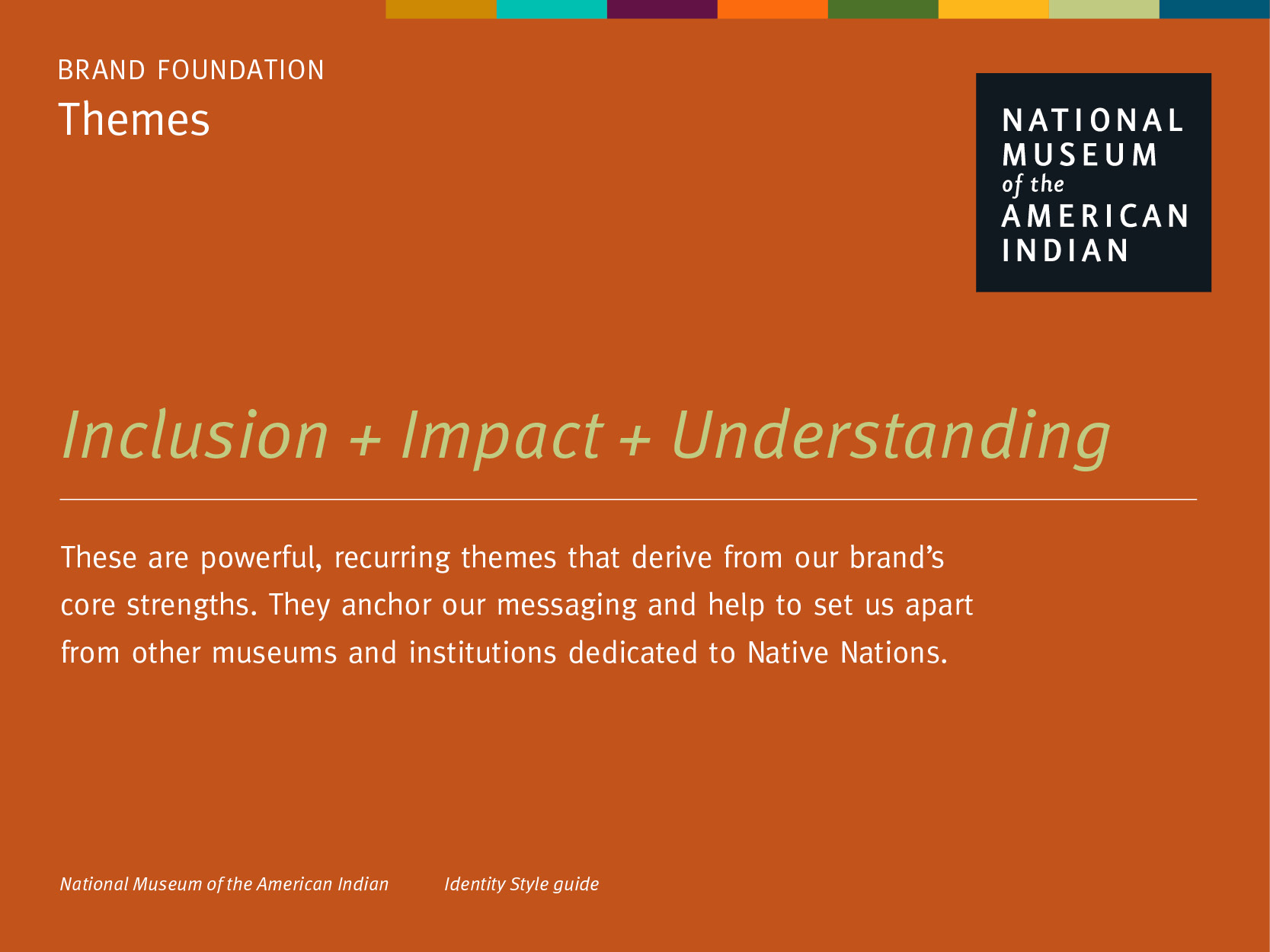

What we call “themes” corresponds closely to what conventional marketers might call “brand drivers.” Whatever the label, in brand development we’re talking about powerful, recurring ideas derived from the brand’s core strengths. These ideas help to unify and focus the other elements of the story—in particular, the value propositions that anchor key messages, including the brand promise. The brand story we developed with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian identifies and develops three themes: inclusion, impact, and understanding.

Second Ring—Primaries: Positioning, Promise, Personality

Moving beyond themes we come to the second ring. We call this the Primaries ring because the three elements that live here—positioning, promise, and personality, are the brand storytelling equivalent of primary colors. For brand marketers, this is familiar territory.

The positioning is the brand’s defining point of difference distilled down to a single powerful idea. In general, a good positioning is one that no other brand can legitimately claim with the same level of credibility and conviction. Of course, a good positioning must also speak to something that matters to customers and is easy to defend in the face of would-be competitors who might wish to claim it for themselves.

The promise is a succinct, highly distilled statement of a brand’s overarching value. A good promise aligns with the positioning and frequently derives from the story’s dominant theme. Ultimately, a brand promises many things to many types of customer at many levels. In developing the promise, we look for the one value proposition that rises above and organizes the others.

The personality profile is a summary description of a brand’s outward style and manner. Like the positioning, the personality plays a key role in differentiating the brand. The positioning does so by means of conveying a powerful idea; the personality by means of creating a distinctive vibe through tone of voice, visual style, and quality of experience.

We look to identify and describe three to five personality attributes to inform how we tell the story. To help writers and designers interpret these attributes, we do more than simply attach dictionary definitions to them. We detail the kinds of perceptions about the brand that we want each personality attribute to evoke. We also detail how we see each attribute shaping visual and verbal expression. To paint a clear picture of what the attributes are, we also describe what they aren’t.

Third Ring—Palette: Logo. Visual Language, Name, Tagline, Descriptor, Messaging, Backstory

The third ring we nickname the Palette. It’s where a host of additional building blocks shaped by the Primaries come together. Many of these are self explanatory. For now, two bear special mention:

First, the backstory. In many ways, it’s our apex deliverable. The backstory tells the story of the organization or offering through the lens of the brand. It brings together all of the other “inner ring” elements of the platform—vision, positioning, themes, promise and so on—into a single unified narrative.

The backstory in its full form, sometimes approaching 1,500 words, doesn’t usually translate as-is for public consumption. In this regard, it’s similar to a movie treatment or the synopsis of a play. That said, the backstory serves many important behind-the-scenes purposes and shapes many market-facing communications.

First, it serves as a mirror against which to hold other communications and initiatives. Do they feel as if they’re a part of it? The backstory can also serve as an onboarding tool. Cut to size and set to images, it can also serve as a powerful tool for motivating employees and partners. In addition, it can be adapted to meet a wide range of communications needs from PR boilerplate and presentation intros to a range of About statements and more.

Before moving on from the backstory, an important distinction to note: The backstory isn’t the same as the “brand story” writ large. The backstory is a tool for giving form to the overall brand much as a treatment is a tool for writing and producing a movie. The “brand story” is a narrative that’s told, sensed, and experienced on an ongoing basis, usually by many people across an array of media, channels, and communications. The brand story endures as long as the brand itself endures. Second only to a life itself, today the brand may be the most diffuse form of narrative known to humans. (In centuries past this probably wasn’t the case, but that’s a topic for another day.)

Crucially, the backstory sets the stage for the messaging framework, the daily workhorse of verbal brand communications. Complementing the backstory,

the messaging framework breaks down backstory into messages based on key brand elements, provides an additional level of detail, and relates this detail to specific audiences to achieve specific communications goals.

Fourth Ring—Guides: Visual Guidelines, Verbal Guidelines, Experience Guidelines

If efforts up through the third ring are about building out a toolbox for storytelling, the fourth ring is about setting down the way to tell it. Most of the time, we develop visual and verbal guidelines together. After all, both are informed by the same brand personality and, to a lesser extent, the other cornerstone elements of the brand. While we call these tools guidelines, we think of them more as cookbooks, providing recipes more than rules. We encourage those who work with these tools to think of themselves as interpreters more than rote followers of formulas. Cooking is an art form that sometimes benefits from substitution and improvisation. The same is true of creating brand communications. As a great creative director, Alfredo Muccino, once remarked to me, “True consistency is consistency of spirit.”

Fifth Ring—Activation: Key Communications, Communications Planning, Content Strategy, Channel Strategies, Coaching & Training, Performance Monitoring

And now to begin to tell the story. Beyond guidelines, this involves planning and strategy—choosing how and where the story will resonate the most. Beyond tools this involves talent and a watchful eye on how the story is playing. It is a story, after all, that will be told and retold, in myriad ways, times and places.

And if the story should bear refining or updating? Back to the brand wheel: With the right kind of intelligence to draw upon, the wheel can serve yet one more purpose: Given the role each of the elements plays in shaping the whole, the brand wheel can suggest where and how to refine a story to achieve the desired results. Information that suggests a muddled story suggests one course of action. A good story poorly told, another. A story that has grown tired, yet another.

Years ago, when we first started work on the tourism and economic development brand for Detroit, one campaign and then another had failed to increase visitation or convention center bookings. Nobody could tell us why. No lessons could be applied from one year to the next. Was the creative flawed, or did the problems rest with the ideas informing it? The only choice at the time was to start again from scratch. The choice now is different. A good brand is the mother of many campaigns and initiatives, each building on the other, increasing the odds of long-term success.